|

| Messier 13: The Great Hercules Globular Cluster |

"For my part, I know nothing with any certainty but the sight of the stars makes me dream." – Vincent Van Gogh

First: apologies for the lack of posts recently. It turns out that "mapping Mars from my back garden" is a tough act to follow; also, the whole lockdown "thing" tends to put a limit on where you can go (on this planet at least).

On the plus side, I'm pleased to say I recently became a contributing writer for the astronomy website Love the Night Sky. If you're new to the hobby, or coming back to it after a break, this site has all the information you need to get up and running. Unlike many other astronomy-themed websites and YouTube channels (which tend to obsess about getting the perfect astrophoto with little or no information about the object being photographed), the emphasis here is on learning and observing: helping you find your way around the night sky, while enriching your experience with scientific and historical context. I've been observing for years, but it's that sense of there always being more to see and more to learn that keeps me coming back to the eyepiece again and again.

My first three articles (with more to follow) are available via the links below, covering some of the finest deep-sky objects you can see though a telescope. Each article explains what the object is, when to see it, how to find it, and what you can expect to see through telescopes of different apertures, as well as links to other sources of information.

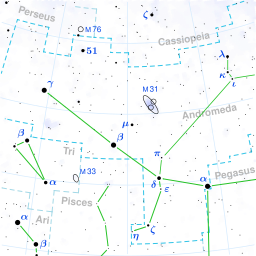

M13: The Great Hercules Globular Cluster (as shown in the image above)

All three of these objects are visible on summer nights, and you don't need a large telescope to see them. So, if the sky is clear and the stars are out, why not grab a pair of binoculars, turn your lights off, and enjoy the view? I could say more, but a certain very famous professor has already said it for me:

"Look up at the stars and not down at your feet. Try to make sense of what you see, and wonder about what makes the universe exist. Be curious." – Stephen Hawking

UPDATE: More articles now available, as linked below:

Remember: a telescope doesn't take up space; it gives you space.